Recent research from Gallup on hybrid working suggests that one of the most important factors for a high performing hybrid team is…

Trust.

That’s not surprising – when managing beyond the line of sight, you are relying on your people to do the work you are paying them for, to the best of their ability – and without the means to track exactly what they are doing all day.

Some companies have approached this problem with activity-monitoring surveillance software or bureaucratic work tracking systems. While this may be appropriate for certain industries and roles, such an approach will compound the lack of trust.

So maybe we could instead look at how to build trust?

Now, trust is a complex emotional dynamic, and so much will depend on the circumstances of you, your team, and your work.

But we can use a tool to help us as managers work out how we can be more trustworthy ourselves, and how to build trust in others.

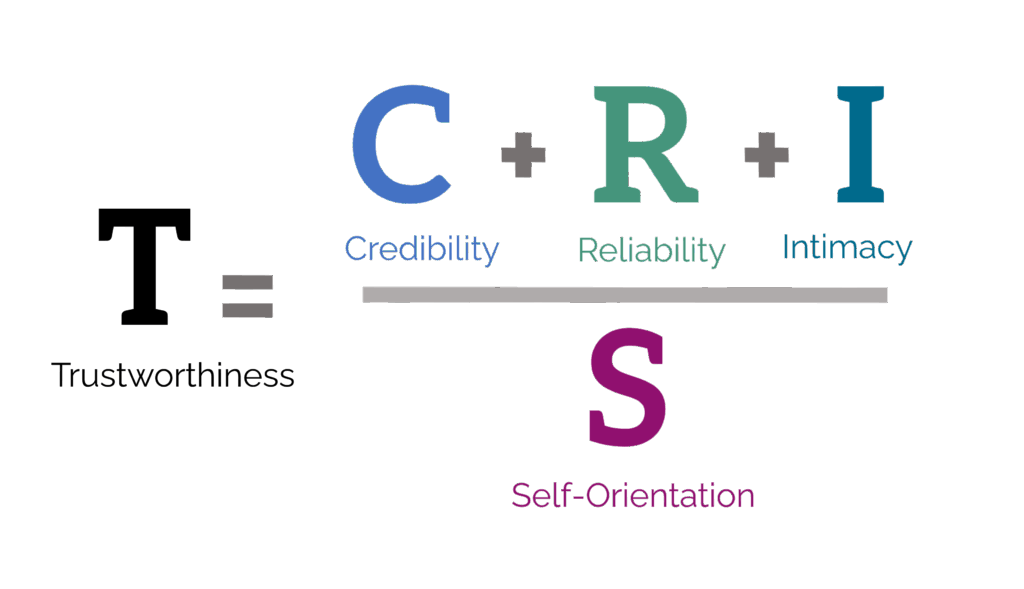

It’s the Trust Equation, developed by Maister, Green and Galford:

Trustworthiness is the sum of three factors:

- Credibility: What you say – your knowledge, experience, and judgment.

- Reliability: What you do – your consistency, your ability to keep promises and be dependable.

- Intimacy: How safe others feel in sharing with you – your ability to be empathetic and respect confidentiality.

However, these three factors are divided by the fourth:

- Self-Orientation: Where your focus lies – on yourself or others.

Using the equation to build trust in a hybrid team

The aim is to consider the factors and focus on what you can do to enhance how others feel about you. It is also about setting up the opportunities for your team members to act in such a way that you and other team members trust them more.

Credibility

You: Be transparent with decision-making in hybrid settings. Share the logic and analysis behind the choices you make.

Enable others: Give staff opportunities to showcase their expertise – to you and others. Create forums (e.g. team meetings, internal newsletters, project showcases) where staff can present ideas, lead discussions, or share insights. Encourage team members to share their strengths and recognise them publicly. Use appreciative language to reinforce their contributions and build confidence.

Reliability

You: Set clear expectations, and standards – for deadlines and availability – and keep to them. Act consistently when assessing contribution and making decisions,

Enable others: Establish workflows and check-in processes that prompt others to be proactive in their information-sharing, that makes progress visible and enables workload problems to be uncovered before they become problematic. Celebrate consistent follow-through and express gratitude for dependability. Link tasks to a shared purpose to motivate reliable behaviour.

Intimacy

You: Create space for personal connection – schedule regular 1:1s, ask about well-being, and encourage informal chats. These are much harder when you see each other less consistently, so pay particular attention here. Share of yourself to the extent that you are comfortable, your openness can encourage openness in others which builds connection.

Enable others: Create space for team members to connect. Create projects or tasks for pairs or small groups. Build social time into your team meetings to maximise the value of your shared time. Foster a culture of appreciation and empathy. Use positive communication to acknowledge personal efforts and create deeper connections.

Self-Orientation

You: Share your intentions, explain why you are asking for something or the purpose behind your decisions. Celebrate others’ wins publicly. Support your people to grow and develop. Be accountable for your mistakes..

Enable others: Ensure team members understand the bigger picture – their role within the organisation and the overall purpose and aims. Set team goals and objectives, and help them see how their individual strengths are aligned. Delegate tasks and meaningful responsibilities. Express gratitude for collaborative efforts and selfless contributions.